Why LLMs Struggle With Financial Data & How We Fixed It

TL;DR

LLMs are great at talking about finance, but bad at doing finance. They predict plausible text, not guaranteed-correct numbers, and they break hard on things like arithmetic, timelines, edge cases, and messy, multi-system financial data.

To fix this, we:

- Stopped letting the LLM act as a calculator or analytics engine.

- Centralized all math and metric logic (MRR, churn, etc.) in deterministic, testable code.

- Built a canonical financial data model and event-sourced pipeline so every number has clear lineage.

Use the LLM only to:

- understand the question,

- plan the query/metric pipeline,

- and explain the results in natural language.

Result: you still get “ask anything” natural-language analytics, but every answer is backed by strict definitions, reproducible computation, and an audit trail instead of vibes.

Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) arrived with a bold promise: turn any question into an answer, any document into a summary, any interface into a conversation. Finance, with its jargon, regulations, and endless spreadsheets, looks like the perfect playground for this kind of intelligence. Ask a model “What happened to our gross margin last quarter?” and get back a fluent, seemingly thoughtful answer.

But finance is not just another text domain. It pushes AI models to their limits. You cannot hand-wave a balance sheet. You cannot “approximately” calculate tax liabilities. You cannot hallucinate a number and still be useful.

As we tested LLMs on real financial reasoning—metrics, ledgers, SQL, period-over-period comparisons, compliance-style questions—we learned a blunt lesson: fluency is cheap; correctness is not. LLMs are powerful interfaces for financial intelligence, but on their own they are unreliable engines for financial reasoning. To make them useful, you have to design around their weaknesses: with structure, guardrails, external computation, and domain-specific logic.

This article walks through why LLMs struggle with financial data, how those failure modes show up in practice, and what a more trustworthy architecture for financial AI looks like.

The Promise of LLMs in Finance

The attraction is obvious:

Natural language interfaces for financial insight

Instead of writing a complex SQL query or building a pivot table, a user says: “Show me monthly recurring revenue by plan for the last 12 months, excluding churned customers.” The model parses the intent, calls tools, and presents the result in plain language.

Automating reporting, forecasting, and compliance queries

LLMs can draft management commentary, explain variances, translate raw numbers into narratives for investors, and surface anomalies. They can turn policy documents and accounting guides into conversational reference systems for finance teams.

Democratizing access to financial expertise

Non-experts like founders, operators, small business owners can ask nuanced questions without knowing accounting standards or database schemas. The dream is: “CFO-level insight without needing a CFO in the room every time you have a question.”

The promise is real. But the closer you get to actual money, the more obvious the cracks become.

Understanding the Limitations

Finance is unforgiving.

Large language models are fundamentally probabilistic sequence predictors rather than deterministic numerical engines.

As a result, they frequently exhibit instability and inaccuracy on arithmetic and quantitative reasoning tasks, especially when multi-step calculations or strict numerical guarantees are required.

Finance demands verifiable logic, not linguistic approximation

In normal language tasks, “good enough” is often fine. In finance, a single wrong sign, off-by-one date, or missing filter can fundamentally change the meaning of a result.

Why most LLMs falter on structured and regulated data

LLMs were trained mostly on web-scale text, not on controlled, schema-aligned, audited ledgers. They don’t naturally respect chart of accounts structures, revenue recognition rules, or multi-GAAP (multiple accounting standards) logic.

Common pain points from early experiments

Why LLMs Are Not Good With Numbers

LLMs are not built to be deterministic calculators. They are built to predict the next token in a sequence. That design choice has several consequences.

1) They learn statistical patterns, not arithmetic rules

LLMs are trained on massive text corpora. They see billions of examples where numbers appear in patterns: dates, prices, percentages, tables, news summaries. So they become very good at number-shaped language. They learn what looks plausible next to what.

But arithmetic is not about plausibility. It’s about rule-following with zero tolerance for “close enough.”

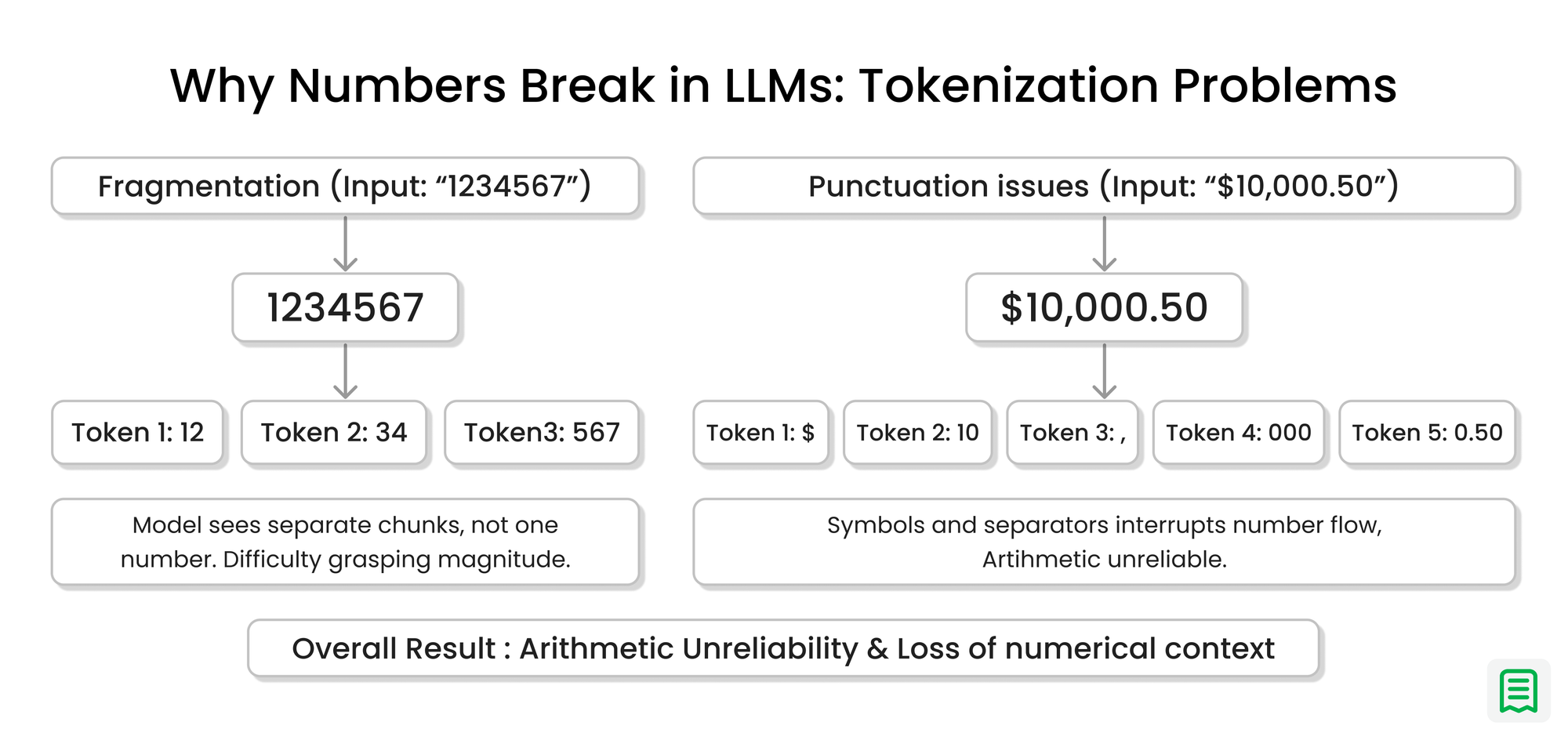

2) Tokenization makes numbers awkward

Numbers aren’t always represented as single atomic units. Depending on the tokenizer:

“1234567” may get split into chunks.

“10,000.50” might become a weird soup of tokens.

That means long numbers are not treated as clean objects with internal structure. They’re treated as text fragments.

So the model doesn’t inherently “see” a number. It sees a string pattern that often correlates with meaning.

3) Precision is not a native objective

During training, the model is rewarded for producing text that matches likely continuations, not for computing exact results. So for many quantitative prompts, the model will round implicitly, simplify, assume missing context or generate the most typical-looking answer. For numbers that drive real decisions, this is dangerous.

4) Multi-step calculations degrade fast

You might get correct results for small numbers, one-step operations, short contexts. But as soon as you add multiple steps, multiple conditions, multiple time windows, or messy real-world exceptions, the probability of a subtle slip rises quickly. LLMs don’t “carry” a reliable internal scratchpad the way a calculator does. They simulate reasoning through text and simulation is fragile.

Why Finance Data Is a Hostile Environment for General-Purpose LLMs

Even if we ignore pure arithmetic, finance introduces structural problems that break casual model reasoning.

1) Definitions are not universal

Ask five companies to define churn and you’ll get seven answers. Even common metrics like MRR are full of policy choices:

How do you treat annual plans?

What counts as “active”?

Are trials included?

How do upgrades/downgrades and proration get normalized?

An LLM cannot safely assume a universal truth here.

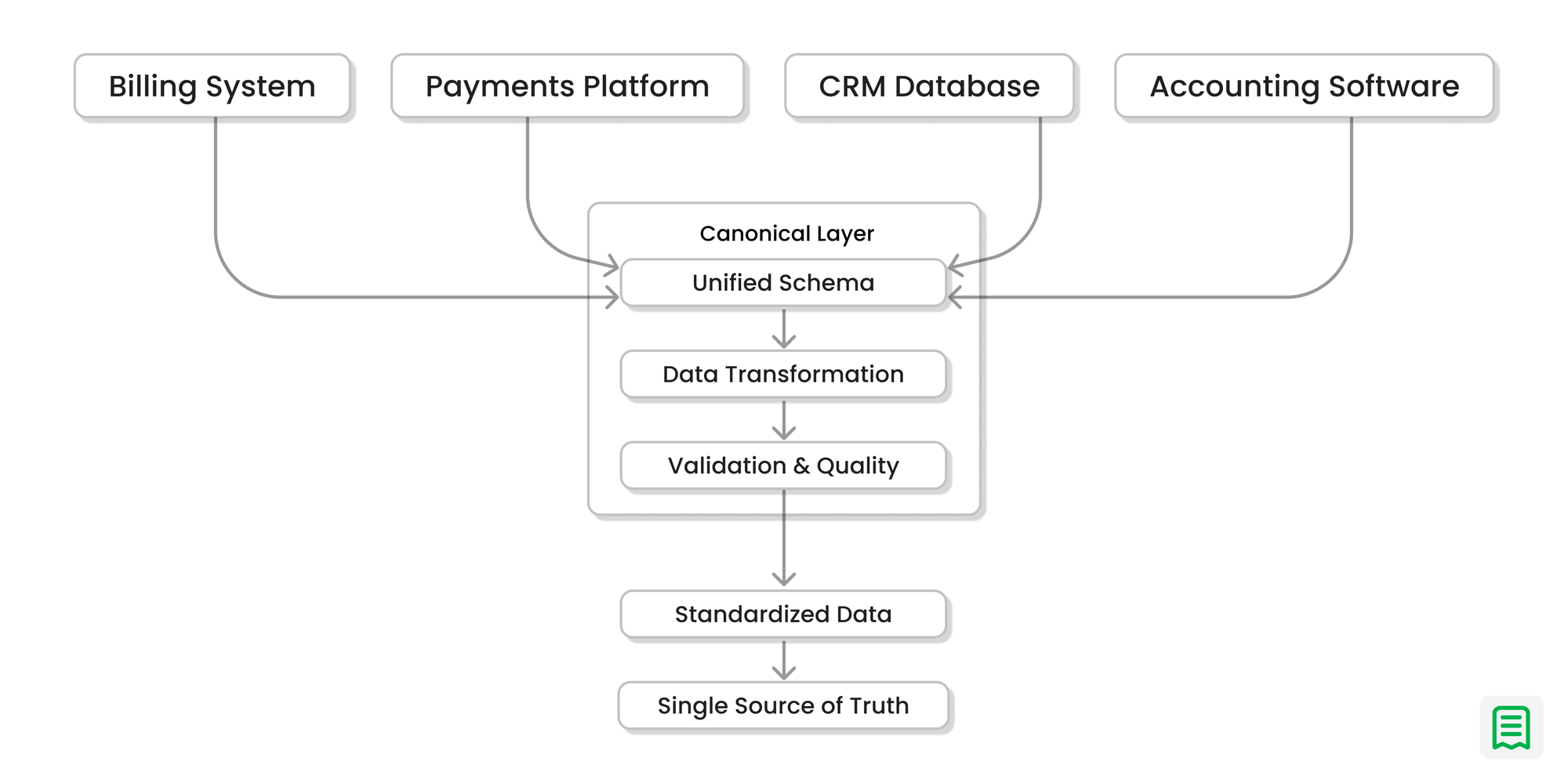

2) Data is fragmented across systems

Real financial truth is stitched together from billing platforms, payment processors, accounting ledgers, CRM systems, spreadsheets etc. Each source has its own schema and semantics. LLMs aren’t reliable reconciliation engines.

3) Precision and data lineage are non-negotiable

In finance, “Revenue dipped in March” is not a meaningful answer on its own. You need to know exactly how much it dipped, which customers and transactions drove the change, and the full lineage of that figure: which tables, which queries, which journal entries, and which business rules produced it.

4) Edge cases are the rule, not the exception

Refunds, credits, partial payments, backdated invoices, currency conversions—these aren’t rare anomalies. They’re normal business life. LLMs often miss them unless explicitly forced to handle each category.

The correct answer is procedural

The real path to truth is a pipeline:

extract

normalize

deduplicate

classify

define time windows

compute metrics

preserve audit trails

LLMs are not naturally designed for stable, deterministic pipelines.

Why LLMs Struggle With Analytics

Standard LLMs are excellent at describing analysis that has already been done. They are far worse at doing the analysis itself.

1) Textual inference vs analytical reasoning

Analytics involves building a chain: select relevant records, aggregate them correctly, apply business rules, compare across time, and interpret the result. This is multi-step symbolic reasoning and not pattern completion.

2) Multi-step logic breaks model flow

Complex questions like: “Compute cohort-based net revenue retention for customers who upgraded from Plan A to Plan B in the last 18 months, excluding one-off enterprise deals” require:

Understanding cohorts

Mapping plans to structured fields

Filtering by time and conditions

Computing the correct metric definition

A plain LLM often drops steps, mis-defines the metric, or silently relaxes constraints.

3) Probabilistic token prediction vs analytical rigor

LLMs decide the “next token” by probability, not by symbolic correctness. For math-heavy and rule-heavy domains, that mismatch matters. An answer that sounds like a seasoned analyst wrote it can still be numerically wrong.

Why LLMs Struggle With Tabular Data

Most financial systems are structured as tables, not prose. Models were never designed to “think in rows and columns.”

1) Tables resist tokenization

When we serialize tables as text (comma-separated values, markdown tables, JSON lists), we destroy some of the spatial and relational structure: which column belongs to which row, the type of each value, and the constraints.

2) Column mapping is critical for financial reasoning

If the model confuses gross_amount with net_amount, or invoice_date with payment_date, the entire analysis collapses. A serious system must anchor the model to a schema and enforce correct column usage, not rely on the model “guessing” based on surrounding tokens.

How We Fixed the Numbers

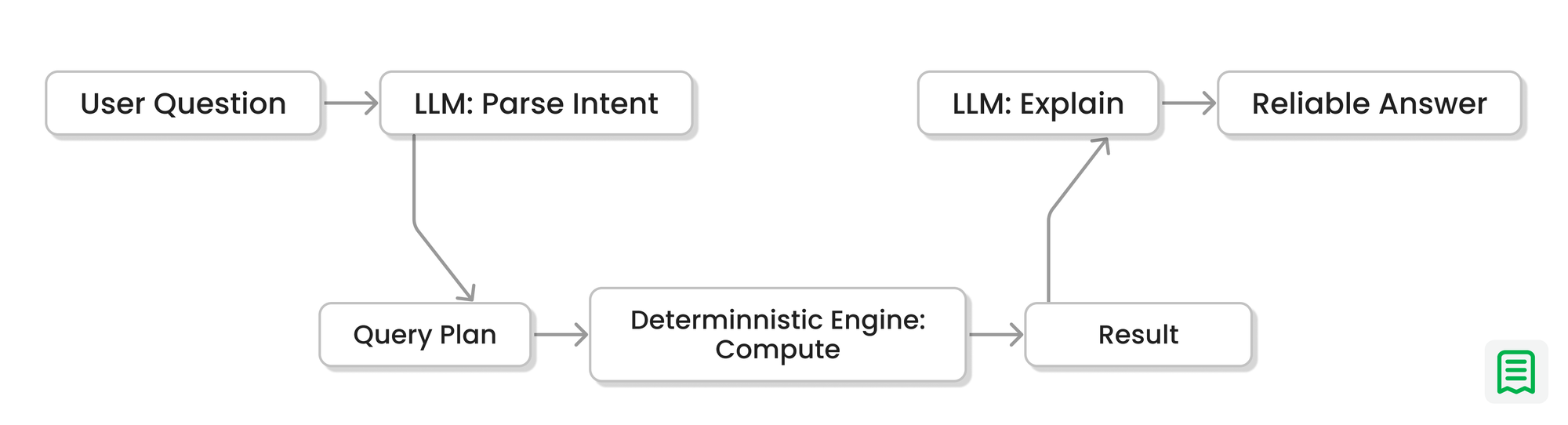

The biggest turning point was admitting a simple truth: An LLM should never be the calculator.

We stopped letting the model “compute” values in free-form text and moved all numeric truth into deterministic code. The model’s job became: select definitions, choose time windows, request the right data, and explain results. All arithmetic moved into a strict numeric layer.

We centralized all math computations in a deterministic engine

We made the LLM output a plan, not a number

Here’s what that means in practice.

What “centralized in a deterministic engine” means

Instead of letting the model improvise arithmetic in its head, we made a small, strict math service whose only job is:

Take structured inputs (numbers + operation).

Run pure functions (no randomness, no guessing).

Return precise outputs, always the same for the same inputs.

The LLM’s job is reduced to: “Understand the user’s request → translate it into a call to the math engine → explain the result.”

A simple example: computing an average

Say the user asks: “What’s the average of 2.3, 5.7, and 9.0?”

The flow looks like this:

1. LLM parses the request

It converts the text into a structured request:

{ "operation": "average", "values": [2.3, 5.7, 9.0]}

2. Math engine does the calculation

The engine has a tiny, explicit implementation:

def average(values: list[float]) -> float:

if not values:

raise ValueError("Cannot compute average of empty list")

return sum(values) / len(values)

For [2.3, 5.7, 9.0], it returns:

{ "result": 5.6666666667}

3. LLM explains the result

The model gets that result and turns it into natural language:

“The average is about 5.67. I added 2.3 + 5.7 + 9.0 = 17.0, then divided by 3 to get 5.67.”

The important part: The only place where the average is actually computed is inside the math engine. The model is just narrating what the engine already did.

By centralizing all math:

Every operation is testable – we can unit-test average, sum, median, etc.

Behavior is stable – changing the language model or its temperature doesn’t change the numbers.

We get one source of truth – any feature that needs arithmetic calls the same engine.

The real moral

We didn’t “teach the LLM math.” We did something better: We removed math from the LLM’s responsibilities.

We built a numeric spine that is:

consistent,

testable,

auditable

and boring in exactly the right way.

Then we let the model do what it’s actually good at:

translating intent into plans,

and results into explanations.

That’s how you get natural-language finance without hallucinating an entirely new reality.

How We’re Fixing LLMs for Real-World Finance

We changed the role of the model. Instead of using the LLM to produce final financial numbers, we used it to plan and orchestrate a deterministic analytics engine.

1) Canonical data model

We normalized multi-provider chaos into a consistent schema for:

customers,

subscriptions,

invoices,

payments,

credits,

and journal events.

This reduces ambiguity before reasoning begins.

2) Event-sourced truth

We preserved raw provider events while also generating derived canonical events. Every number can be traced to its source.

3) Deterministic metric definitions

We codified MRR, ARR, churn, and revenue churn as explicit rules in code. The model doesn’t invent the rules. It selects the correct rule-set and parameters.

4) Query planning + execution split

The LLM generates a structured query plan. Our engine runs it on real data and computes results deterministically.

5) The model returns to its true superpower: explanation

Once the numbers are computed, the model becomes incredible at:

summarizing trends,

explaining drivers,

translating results into human language,

giving investor-friendly narratives.

So we get clarity without sacrificing correctness.

What this unlocks

This architecture gives the best of both worlds:

natural language analytics,

plus definitional rigor,

plus auditability.

Teams can ask complex questions conversationally while trusting that the answer is grounded in consistent policies and deterministic math.

11. Wrapping Up

LLMs are extraordinary at prediction. They guess the next word with uncanny skill. Finance demands something else: understanding, reasoning, and verification.

To make AI reliable in financial decision-making, we have to stop treating LLMs as omniscient calculators and start treating them as what they are: powerful but flawed language engines that need grounding, tools, rules, and oversight.

The path forward is not chasing ever-bigger models in the hope that the hallucinations somehow vanish. It is designing systems where:

Numbers come from deterministic computation

Logic is explicit and testable

Explanations are traceable back to data

Humans remain in the loop where stakes are high

In other words: move from opaque prediction to transparent reasoning. That is what it will take for financial AI to be not just impressive, but truly trustworthy.